* Author’s Note: This article is the second in a series that will explore actionable policies and steps to rejuvenate the inner city and empower the people living there to build a better future for themselves and their families. You can access the first article at https://newsweed.com/the-inner-city-solutions-to-save-americas-soul/opinion/.

Wasted Taxes?

Over the course of several decades, there have been multiple attempts at the federal level to address long-standing poverty issues in

inner-city neighborhoods of our largest metropolitan areas. President Bill Clinton enacted his Empowerment Zones as part of his Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, targeting impoverished areas with block grants for investments alongside tax breaks for businesses. Most recently, President Trump created Opportunity Zones (OZ) under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which was signed into law by Trump on Dec. 22, 2017.

Yet, at best results are mixed, and at worst, these schemes might be an utter failure. An Urban Institute report found that “[A]s OZ incentives are not structured to encourage resident or community engagement, mission-oriented projects struggle to compete for attention with higher-return projects–for which OZs provide much larger subsidies because of the design of the incentive,” the report said.

There are, in fact, a host of problems with OZs. To begin with, there is a lack of appropriate oversite. In the article Opportunity Zones: Gentrification on Steroids?, a Rice University (Houston, Texas) publication under the auspices of the Kinder Institute For Urban Research, Willaim Fulton points out: “ There’s no limit on the amount of investment – or the amount of capital gains deferred and forgiven. And there’s almost no way for a city to track opportunity zone investment. No government agency other than the Internal Revenue Service need be informed that an investment is made.”

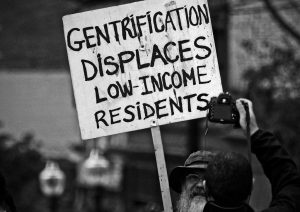

Taxes Used for Gentrification?

Moreover, the report concluded that there’s “ . . . no question that – whatever hope they hold to improve underserved neighborhoods – opportunity zones also hold the risk of accelerating gentrification in Houston. Gentrification is typically defined as a situation where longtime residents of an underserved neighborhood are squeezed out by rising property values that result from new investment.” The bottom line is that this phenomenon of gentrification of Houston can likely be generalized to other places. If so, they will undoubtedly not serve the supposedly targeted population that is actually in need of the program.

It gets a little ugly if you dig a little deeper. As cited in Market Watch, “[I]n booming cities like Denver,” concludes an analysis by Sophie Quinton for Pew Charitable Trusts, “the federal government may end up spending more money on tax relief for pricey apartment buildings, offices and hotels than on tax relief for community-focused but less profitable assets, such as affordable housing.”

It seems that the profit motive being tapped to improve inner-city neighborhoods may also provide perverse economic incentives. As David Yaffe-Bellany of the New York Times states, many wealthy investors “are poised to reap billions in untaxed profits on high-end apartment buildings and hotels in trendy neighborhoods, storage facilities that employ only a handful of workers or student housing in bustling college towns.”

While partisans might claim this is due to Trump’s inept nature or penchant for corruption, Clinton’s plans did not prove effective either. In fact, these schemes seemed to have been colossal failures if you measure their overall impact on distressed communities. As cited in the article Elite Empowerment by Michael Weaver in the publication Jacobin, “In one of the more sanguine assessments, urban scholars Michael J. Rich and Robert P. Stoker found that although ‘several EZ cities produced improvements in their distressed neighborhoods . . . The gains were modest.’”

Weaver goes on to say “The evidence suggests that Clinton’s characterization of empowerment zones as a boon to African Americans is spurious. While the EZ areas outperformed the comparison areas in terms of poverty, the percent of people impoverished still spiked in both.”

New York in particular struggled with implementation of EZs as reported in the City Journal article Where’s the Power in the Empowerment Zone?. “Unless steps are taken soon to revise the New York City empowerment zone plan, the Clinton Administration’s principal initiative in New York City won’t make a nickel’s worth of lasting difference,” wrote the article’s author, Mitchell L. Moss.

Using Taxes Wisely

From my perspective, these types of programs fail, or at least partially fail, because they inherently violate the principles of simplicity, clarity, and priority. Specifically, these programs often empower agencies, individuals, and investors not directly or indirectly connected to the targeted communities, thereby bypassing the opportunity to directly empower the actual residents living there.

With the funds that investors provide and the regulatory guidance that local governments give, small businesses find their access to capital limited. Moreover, the more actors and moving parts in a program, the more complex it becomes. This complexity not only makes a program unwieldy and inefficient, but also makes it more vulnerable to waste and corruption.

And when that many people have their hands in the pot, clarity of purpose becomes fractured as each person acts in their own interest to stare the ship in a direction that personally favors their position. The same is true regarding establishing priorities, which are enmeshed in the shifting sands of the often hidden agendas of the investors and regulators.

Using Taxes with Simplicity, Clarity, and Priority in Mind

What is called for is a more elegant, direct method of lifting the people at the margins of society. My approach, for lack of better terms, would be called the Community Direct Investment Model. (No, it has no connection to the Community Reinvestment Act.) It would work by directly empowering individuals, or groups of individuals, to establish, maintain, and grow their businesses without outside influence or interference.

First, individuals (or small groups of individuals) that either have established businesses or plans for a business, would receive federal grants that align with their goals. (States would have the option of matching or supplementing these grants.) As such, grants could range from a few thousand dollars to much larger sums. The business owners (or-aspiring owners) would have to submit business plans that explain the nature of the business and demographic statistics. As an added incentive, employers would receive additional funds for each new hire that stays employed an entire year, with the stipulation that the monies be spent on improving or expanding the business.

One mechanism to support this endeavor would be receiving support (planning, training, continuing education, accounting guidance) from the Small Business Administration, which would be funded by the grant. Once approved, owners would be able to apportion the funds according to their business plans, with some flexibility to accommodate changing situations.

As a condition of receiving the funds, owners would be required to hire people who live directly in the community. To bolster this effort, neither owners nor their employees would pay any federal taxes (Individual Income Taxes or Payroll Taxas) for a period of three years; but employers would regularly contribute a small amount to an investment fund managed by a local bank or community investment entity.

This investment element would be composed of and overseen by knowledgeable members of the targeted community with the goal of providing financial, job, and technical training as needed to the owners and their employees that are involved in the grant. Outside investors would be welcome to be a part of these ventures but would have little input or control over their invested funds, the future of the fledgling businesses, or receive any financial returns, which would attract people and organizations with a philanthropic mindset rather than strictly a profit motive. These investors would receive a significant tax write-off or credit, however.

At the end of three years, viable businesses would start to pay a small amount of federal taxes graduated over a five-year period, until they are paying the full amount required by law, minus standard business deductions. The costs of this approach would be more than realized as businesses become profitable and eventually not only pay full taxes but employ people from the community who also pay taxes.

In this manner, the community and local businesses control the direction and fate of businesses, resulting in direct empowerment of individuals. As businesses grow, they draw upon and invest in human capital, which builds not only economic incentives for new businesses, but acts as an incubator for talent development, thereby directly regenerating struggling communities.

Mike Gibbons, co-Founder at Culture Assassins, a media company dedicated to “preventing the destruction of healthy, high-performing organizational cultures” frames it this way in his article What Is Human Capital Management & Why Is It Important?: “Smart leaders are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of human capital management as a competitive advantage. The data shows that companies that focus on engagement, well-being, company culture, and employee development in their organization tend to outperform their competitors.”

While I am sure there are some technical flaws in my proposal that need to be tweaked, the overall design and thrust are not only simple and clear, but prioritize the people and communities in need of help in a targeted, straight-forward approach that honors their integrity and gives them a rightful place at the economic table. It’s time for our smart leaders to make smart decisions. It’s time to create and implement the Community Direct Investment Model.